Economic Implications of the One-Child Policy

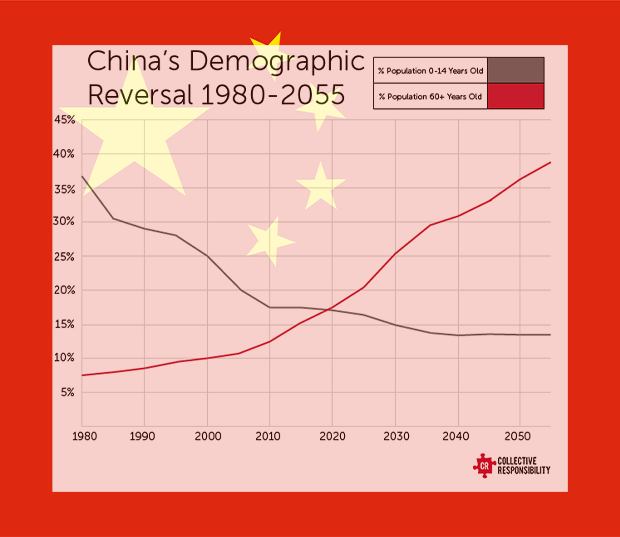

By 2050, 25% of China’s population will be over 65 years old. This situation is the number one economic problem that China will face moving forward.

How did China get here? During the Maoist period following the famous words “more people more power” the nation became the most populous nation on earth. The obvious challenges of unchecked population growth resulted in the ‘one child policy’ in 1979. In 2016, this policy was changed again, allowing for two children per household. If able to pay the requisite tax more children are permitted. Today, China is at a turning point and staring into what the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) has described as ‘unstoppable’ population decline. The Chinese population is hemmed in from two sides, decades of declining birth rates on the left, and steeply rising life expectancy (improved medical technology, improved nutrition) on the right.

The CASS predicts that China’s population will peak in 2020, at 1.44 billion. It’s expected that this will usher in a period of ‘negative population growth’; by 2065, the population is expected to have returned to. Mid-1990’s population levels. A shrinking population may argue a shrinking economy as well.

There are indicators this is already happening. Look at the last four years of Chinese national birth rates:

2016: 17.9 million births

2017: 17.2 million births

2018: 15.2 million births

2019: 14.6 million births

These national figures, striking as they are, hide some of the most significant changes occurring in the provinces. Some areas are reporting birth rate declines as steep as -35% per year.

Despite the fact that China increased the official child-per-family policy to two children in 2016, Chinese families have not rapidly moved to increase in actual size. There are both sociological and economic reasons at play. Women have found an important place in China’s economy and are reluctant to sacrifice a position they have worked hard to attain. After all “women hold up half the sky.” Despite the systemic, positive discrimination favoring male students, more women than men attend Chinese universities. Women are responsible for 41% of Chinese GDP–the highest proportion in the world. Some 7 in 10 Chinese mothers work. Eighty percent of all female self-made billionaires, globally, are Chinese. While Chinese women have earned hard-won economic success, Chinese employers frown on the idea of their female employees taking more time from their jobs to have a second child.

Today, there is a massive in-balance in the number of males versus females in China. Males outnumber females by 34 million people. This problem also arose during the official one-child-per-family era. During this time, male children represented a greater economic advantage than female children. Faced with the one-child policy, sadly, many families chose to abort female babies despite the fact to do so violated Chinese law. Today, there is a massive in-balance in the number of males versus females in China. Males outnumber females by 34 million people. Presently, there are 24 million single men of marrying age in China who cannot find wives – this is the combined population of Texas and New York state. China is already paying a heavy social price for this. Multiple studies implicate gender imbalances in maladies including reduced consumption and real estate bubbles, and correlate with spikes in violent crime, spousal abuse, trafficking and prostitution.

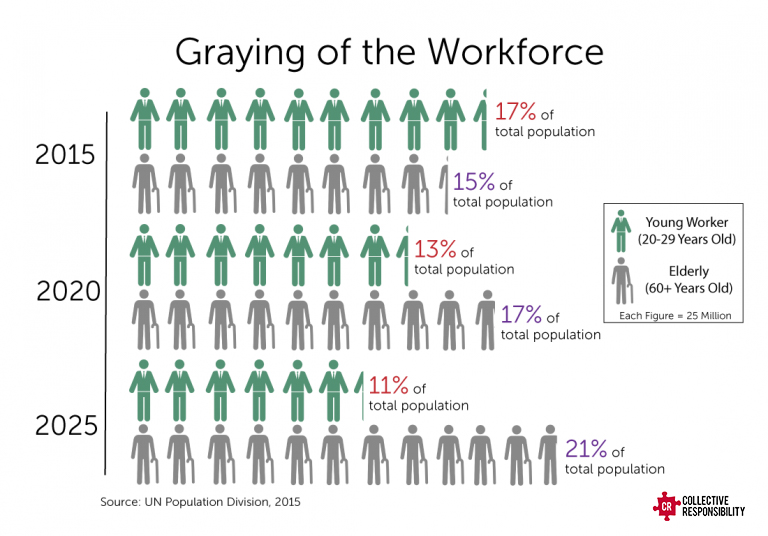

Young Chinese couples are also struggling with economic pressures, including rising education and housing costs. It’s hard to support one child, let alone two. Biology also plays a part; the policy change is only several years old. These young couples grew up during a period when it one child families were the universal rule; larger families represent an uncomfortable change for them. In addition, many of China’s women have passed their peak fertility age. Another major economic challenge is China’s pension shortfall amidst an aging population. Current projections show that China’s pension funds will run dry by 2035. With no pension funds available, young couples will face the economic pressure of supporting eight grandparents and four parents. The problem is especially acute because these young men and women have no siblings of their own to help shoulder the costs.

The future that China is quickly approaching is not one that matches China’s aspirations for global supremacy. Instead, the picture that Beijing’s National Academy of Economic Strategy. Paints features a society where its younger people are burdened by the care of elderly parents and grandparents, living in an economy that is crippled by unsustainable debts. Again, signs of this economic weakness are already at hand; China’s pension shortfall topped $130 billion in 2019, further adding to the nation’s debt burden which is already estimated at three times its GDP. As China moves into the future, this situation may become untenable; in 2014, there were 880 million working adults in China. By 2050, that number is projected to fall to 570 million. This situation also presents a massive macro-economic question: how will China create the required demand for housing, consumer goods and so forth?

Staying abreast of what is happening in China is critical for any organization that aspires to operate there. For over 20 years, Word4Asia has helped our clients legally and successfully navigate in this fascinating and challenging nation. If your plans include work in China, we’d appreciate an opportunity to learn more about where you’re going. We may be able to lend you the support you’ll need to achieve the success you’re aspiring to. Contact Dr. Gene Wood at gene@word4asia.com